Part One

White Nationalism, that proverbial pimple on the ass of the American public, reared its imbecilic head and began to fester anew in Charlottesville, Virginia last weekend. The overwhelming majority of thinking Americans were quick to condemn these miscreants and their perverted racism in the wake of the mayhem they wrought, as they should. Many were quick to ask that our president be more forceful in condemning and repudiating such backwardness, and they have every reason to. Many made pleas that we as Americans openly discuss in a peaceful way our differences, which is proper. Many seem to think that the ideology of white nationalism stems from a celebration of the Confederacy and that effacing all vestiges of its memory is a solution to the proliferation of ignorance and hate among a small but vocal portion of our society. They are dead wrong.

The degenerates that go around spewing hate and taking pride in the purity of their white skin (a laughably absurd notion given the “mongrel” nature of the “white race” due to the multiple Germanic and Anglo-Saxon tribes from which it traces its lineage) do not represent in any shape, form, or fashion anything in the American past. They have a distinctly modern agenda and have simply coopted symbols from our history and tied them into their sick notions of a new American society. It is perhaps appropriate that they fly the Nazi swastika—there is a semblance of commonality in their agenda and Hitler’s evil 20th century plans—but they also are fond of flying the Confederate flag and, in KKK-like fashion, prominently brandishing the Christian cross as they condemn blacks, Jews, and a host of others to which they feel superior. We have heard nobody (yet) allege the root cause of all this backwardness is the church, nor say we should remove all Christian symbols because of their misuse. Nor should we. So I have to wonder why effacement of all controversial symbols from our past is viewed as a solution to deviancy when the people employing them are likely as ignorant of the history they represent as the general populace. What do we do the next time some other misguided group latches onto other historical symbols and personalities—do we remove any mention of them as a consequence as well and think we solved the problem? The trouble is, you see, we have quite a bit of unsavory history that hate groups could utilize in their scheming.

The deep, substantive, and emotional debate taking place in this country over the place of controversial historical symbols is healthy. Understanding our complicated and troubled past and how we remember it are some of the most important discussions we can have. But as a historian who seeks to understand the past first and foremost rather than justify heroes or condemn villains I am increasingly troubled by our selectivity in dealing with such symbols. Perhaps it is because the Confederacy was defeated and its cause lost—a morally bankrupt one which needed to be defeated—it has become a scapegoat for all that is wrong with America’s past. Judging by the narrow focus of our effacement efforts, I can’t help but think someone with no knowledge of American history dropping in on us might reasonably assume that racism and slavery were invented in 1861 by a cabal of angry Southern plantation owners, and that with the defeat of the Confederate armies by the enlightened United States in 1865, both those evils were forever vanquished in America and the nation returned to the racial progressivist continuum initiated by its founders.

The cold, hard truth, however, is that slavery and racism predate the Confederacy by centuries, and the institution was profoundly part and parcel of America’s development for hundreds of years prior to secession. It is good that this fact bothers us, but blinding ourselves to it so that we can isolate a handful of villains in a four-year period among centuries of misdeed is an exercise in willful ignorance and misinforms us and, potentially, future generations. Slavery is an ancient institution forged on populations across the globe. Forcing people to labor against their will for the profit of others has been a terrible result of human greed and misuse of power for as long as there have been humans on the planet. It has rarely been about hate per se, but has always been about power.

We in America like to think of ourselves as descended from an exceptional heritage among the world’s nations, though, and that from the time of the landing of the Pilgrims our national story has been one continuous sweep towards “liberty for all.” We do not like to be reminded that slavery was a foundational element of our nation’s economy from its earliest colonial days, or that it was sanctioned in our constitution, or that many of our early leaders were associated with it to varying degrees. They could scarcely help being so mind you—it was in the very fabric of American society despite their grandiose claims. Whether in the North or South, the East or the West, or an urban or rural location, there is scarcely a place in our great country unconnected with the barbaric institution in some way. In truth if you look for an American past unblemished by the taint of slavery you are on a fool’s errand. Yet we as Americans have usually chosen to believe more in the statements our ancestors made about liberty than denigrate them for their own shortcomings or curse them for being products of their own time, and it has been to our benefit as a nation.

So does all this mean that we should give the Confederacy a pass, and venerate its leaders unquestionably and overlook the fact that its military and political leaders engaged in what could be described treason and, had they won the war they waged, would have certainly kept blacks enslaved for at least another generation? Of course not! But we should acknowledge the fact that Confederates were a lot more in the American mainstream of their time than we are comfortable in admitting, that they fought for a complex variety of motivations and that most conceived their fight being predominantly one for home and hearth, and that they were not necessarily of one mind about the future of American race relations. We would also do well to remember that there are great differences in the rationale and timing of monuments, memorials, and other commemorations of the totality of their lives and deeds. Maybe many of the statues of them can ultimately be best displayed in a new context or location or in some cases removed forever. It is a debate we should have as a society and that historians should have a voice in.

But what we simply cannot do is to allow perverts and deviants to tell us as Americans how we remember and interpret our own history. We can’t have knee-jerk reactions to remove symbols appropriated by these people thinking the symbol gave them the idea for their evil thoughts and deeds. People in our past should be judged and understood in the context of their times. White Nationalists should be judged in their own in similar fashion, a time in which the bigotry they espouse has been clearly repudiated and their dim vision of a future America recognized as a darkly revolutionary and terribly aberrational notion not linked with any historical reality. Let’s judge them for the pathetic views they advance, and leave the Confederacy—and any other era of American history—out of it. American history is not all glorious and enlightened, but it has little connection to the genocidal agenda on display this last weekend and we merely make ourselves feel temporarily better by pretending that not remembering our most difficult moments from the past will solve our problems today.

JMB

Part Two

Like most everyone else on the planet, I felt sickened by the events of the past weekend in Charlottesville, Virginia. Watching white supremacists gather and spew their hate-filled language and rhetoric makes one simply shake their head and question humanity. To think that these sort of rallies can still draw scores of people in the year 2017 baffles the mind. Violence is all that will come from such gatherings.

So much has been written and said about the evils of these white supremacists and the responses to them that there is no need for me or anyone else to say much more. I want to briefly focus on the aspect of symbols and their part in this drama and the relationship to my white Southern heritage. I am fearful that my words will mark me as a Neo-Confederate, which I am not. I am simply a white Southern male who was raised to have an appreciation and respect for soldiers in the Confederate Army who fought, according to the vast majority of evidence, to simply defend their homes. Watching these idiots and their continued use of Confederate flags as their symbol sickens me! Granted, I am a white Southern male, and therefore, approach these symbols from a different perspective than my fellow black Americans. But to me, that flag does not represent white supremacy but was simply the flag carried by scores of men who fought primarily for a cause other than simply the desire to defend slavery and white supremacy. I understand that millions of black Americans see the Confederate battle flag as a symbol of white supremacy. Nowadays, it has become impossible to display that flag without that being the dominant expression. All I can say is DAMN those who after the Civil War hijacked that flag to represent their cause of white supremacy and racism.

Beginning as a youngster, I have enjoyed reading military accounts of the battles of the Civil War and was amazed at the accounts of strategy, tactics, and extreme bravery by my Southern ancestors. Nowadays, I am sometimes made to feel guilty to have enjoyed my reading of the war as it seems to place me in this group of white supremacists who still desire to fight the war and promote their racist demagoguery.

I want to scream at these idiots and say their ridiculous actions will only bring about the demise of monuments and symbols which they claim that they want to protect and save!!!! But the removal of these monuments and symbols is the only possible outcome when these morons link statues and monuments to the cause of white supremacy and even worse, link it with the Nazi flag, the ultimate symbol of racism and hate!

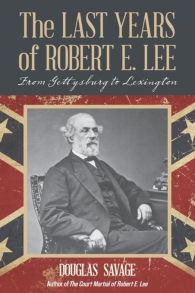

A statue of Robert E. Lee served as a backdrop to the actions this past weekend and I am convinced that he would strongly disapprove of the actions of those who want to use his image and statue to further their cause!!

CPW