I want to love house museums, and in theory I should. They should be, after all, time capsules where lives from the past were actually lived, where historic objects are displayed in proper context, and the diversity of interpretation is as broad and varied as the experiences of the many people who have lived in them. I hate to admit it, but I nonetheless find a lot house museums a bit disappointing.

For one thing, the interpretation they offer can be alarmingly standard, especially in the South where I live and “historic” often means “antebellum.” When one visits so many of the historic homes here, you almost invariably discuss the ornate parlor, the high ceilings and central hallway to promote ventilation, the detached kitchen and the reasons why this arrangement was so, the sitting room and the “ladies’ parlors”, the ubiquitous courting sofa and rope beds, the fact that slaves probably helped in construction of the home, and on occasion, the dubious legend of taxation based on number of closets. And we can’t forget the unfortunately mind-numbing recitations on the provenance of the elaborate antique furnishings scattered throughout, most of which very often have nothing whatsoever to do with the house. In fairness it can all be very compelling depending on the objects, the story, and the guide, but it can also seem frustratingly generic, focusing on Victorian era symbolism and an artificial polished presentation for entertaining guests to the point that imagining anyone actually living in such a staid museum atmosphere seems difficult. Despite the best efforts of staff, few historic homes I have visited ever really strike a chord to those like me seeking a little more in their heritage tourism experience.

I have wondered why this should be the case from time to time, but have only recently been able to put my finger on why. I have found that I am personally interested in historic homes more as places where history happened—historic sites—than examples of any particular style or era—historic museums. Consequently, I have found that I find single compelling moments that occurred within historic homes are what prompt me to connect with them on a more meaningful level than any awareness of craftsmanship of its architecture or the elegance of its furnishings. In truth one of my favorite “house museums” of all interprets a house that is actually no longer standing—Ben Franklin’s house in Philadelphia. A ghost structure stands atop its former site, with the location of rooms and quotes from Franklin’s diaries engraved in the pavers visitors walk on as they explore its footprint. I remember more about that house as imagined in my mind’s eye that most I have physically toured.

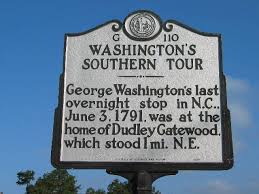

I have visited a lot of house museums, but the ones I remember the most are those that capture some particular moment with such clarity that the rest of the structure becomes context, such as the Potts House at Valley Forge set up as the frenzied headquarters of George Washington during that pivotal winter at Valley Forge, the unfinished upper floors at Longwood in Natchez, where work was halted at the beginning of the Civil War, or the parlor of the McLean House in Appomattox where Lee surrendered to Grant. This may seem a pretty narrow mission for most house museums, as not every location is equally equipped to interpret such evocative moments. But the effort to capture a particularly poignant event is the point.

None of this means I question the validity of house museums that interpret daily life of people who are not as famous as Washington. I believe there is definitely a place for the preservation of specific homes as “best examples” of architectural styles or illustrative of lifestyles from the past, for on my list of most memorable house museums is also Drayton Hall in South Carolina, which features unfurnished rooms on its tours.

But the house as a historic site, providing a special connection to the past through the stories of events that occurred within it in the past, even if momentary, is what sparks my deeper intrigue with a historic house museum. I guess I am one of those for whom “Washington slept here” still resonates. But I don’t think I’m alone.

JMB