Author John Winkler adds to his collection of military campaign narratives through Osprey Publishing with his Tippecanoe 1811. Similar to his books Wabash 1791 and Fallen Timbers 1794, Winkler analyzes the campaign and battle in the Osprey format and provides a general overview of this dramatic encounter which altered the course of American history.

Following the American victory over a Native American force at Fallen Timbers in 1794 and subsequent Treaty of Greenville in 1795, the United States continued to acquire further land cessions through additional treaties with the region’s Native Americans. By the early 1800s, many natives had become angry over Americans constant grasping of land and through the efforts of the famed Shawnee leaders Tenskatawa (the Prophet) and Tecumseh, decided to stand up to this growing encroachment. Indiana Territory Governor William Henry Harrison witnessed the growing tensions and the Native American build-up at Prophetstown and determined to disperse them. Tecumseh, busy with visiting other native groups to build a comprehensive Native American confederacy, told the Prophet not to bring on any engagement until he returned, a directive that the Prophet failed to heed which set the stage for the dramatic encounter at Tippecanoe.

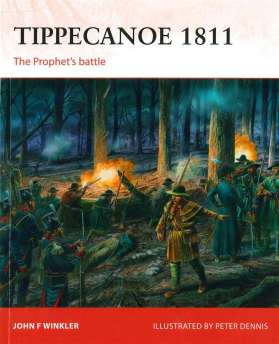

Writers for Osprey Publishing follow a pre-determined format for their campaign narratives which breaks down campaigns in approximately 100 pages under the sections of Introduction, Chronology, Opposing Commanders, Armies and Plans, Campaign and Battle, and finally Aftermath. Using this model, Winkler provides background and traces the movements of the leaders and forces until discussing the dramatic battle itself on November 7, 1811, when the Prophet’s forces staged a daring night attack on Harrison’s force. With detailed maps and full color illustrations, readers follow the nearly three hour attack which failed to destroy Harrison’s men. Harrison’s army would go on to destroy Prophetstown, delivering a near fatal blow to the burgeoning confederacy. Upon learning of the battle, Tecumseh remarked about the “fruits of our labor destroyed.”

Tippecanoe 1811 is an overall quick and enjoyable read, meant to simply provide a brief summary of the campaign and battle. It does seem at times that the format shoehorns writers and prevents perhaps a better written narrative. This format also does not lend itself to provide the background necessary to discuss adequately the complexities of the efforts of Tenskatawa and Tecumseh as well as discuss how those efforts affected the countless thousands in the region. Osprey books serve a purpose in providing military campaign overviews in an interesting and graphically appealing format which pleases many of their devout fans. If one is looking to gain a more in-depth analysis or larger narrative on events like Tippecanoe, then readers simply need to go elsewhere.

CPW