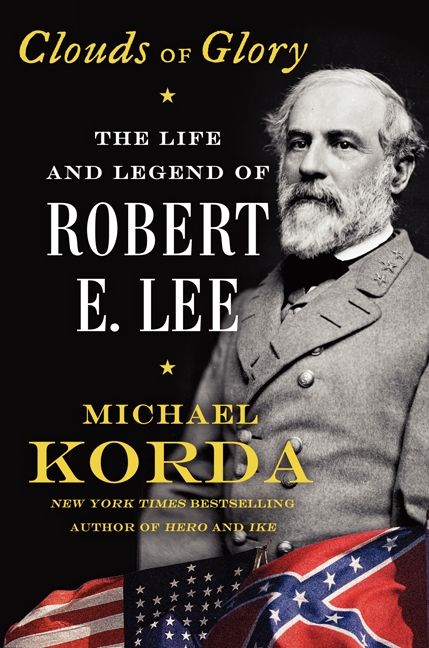

Michael Korda’s Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee attempts to provide a comprehensive new study of a man who is among the most analyzed leaders in all of American history. This task would on the surface to seem difficult at best for many obvious reasons, both for the sheer volume of available works on the subject and the fact that Lee just happens to also be one of the few historical figures about whom there has been remarkable consistent consensus among historians for nearly a century. Scholars ranging from Douglas Southall Freeman to Thomas Connelly and from Emory Thomas to Elizabeth Brown Pryor, writing in different era and from different points of view and with varying emphases, have consistently found Lee to have been exceptionally talented as a military leader with a unique ability to inspire the best performance in those he commanded; remarkably devoted to duty; and a master of self-control even in the most difficult of circumstances. They have also found him to be thoroughly a man of his age in thought and outlook despite his basic decency, unwilling or unable to countenance the actual equality of all men even if he could perhaps respect their basic humanity a bit more than many of his peers. Sure, a few marginal studies have attempted to paint him as a typical racist slaveowner and simple rebel traitor on the wrong end of a war and history, but serious historians seem to have always known the story is more complicated than that.

So what could yet another biography of such a thoroughly understood man possibly contribute that will be new? Not much as it turns out, even if it weighs in at a door-stopping 785 pages. I will be the first to admit, however, that whether or not a book offers a “new” understanding of a subject is usually a pretty shaky criterion upon which to judge the merits of a historical narrative. Some stories are so central to our national historical drama that they merit retelling every once in a while with fresh eyes or a different emphasis. This is precisely what makes Clouds of Glory worth the read. In it Korda attempts to explain why Lee’s name still looms so large in American history while he attempts to disentangle the real Lee from the Lee of legend. In its pages he details Lee’s life from his somewhat aristocratic upbringing in tidewater Virginia to his death while serving as the president of a college that today bears his name, in the end demonstrating that the man and the myth are actually hopelessly entangled.

In all honesty, Korda’s book is an unabashedly admiring biography despite its pretenses at objectivity. The author lauds Lee’s abilities in a variety of endeavors throughout his military and civilian careers, going to great pains to demonstrate that he would be a man worth remembering in American history had the Civil War never even happened. There is some truth in this, as his sterling record of service as a United States soldier and engineer were indeed exceptional. He helped construct important fortifications from the coast of New York to Georgia; diverted the course of the mighty Mississippi and thus helped ensure the economic stability of St. Louis in the process; won the accolades of his superiors for his exemplary service and accomplishments during the Mexican War; rendered stoically admirable if uneventful service on the plains of Texas; and of course served as the superintendent of West Point Military Academy. But to his credit Korda is also candid about Lee’s shortcomings and failings. He discusses with clear-eyed candor his disastrous military decisions that led to the deaths of thousands of men at Malvern Hill and Gettysburg, his perhaps irrational belief in the near-invincibility of the men he commanded, and the troubles arising from his passive leadership style which eschewed direct confrontation in place of encouragement to follow his example in devotion to duty.

Korda goes into perhaps excessive detail in explaining the most delicate aspect of Lee’s legacy, and the sole reason his continued veneration is sometimes greeted with surprise in contemporary times—Lee accepted and in the end worked to advance the institution of slavery, whether he relished it or not. How did Lee really regard African Americans? What did he really think of slavery? What role did his thoughts on these subjects play in his decision to take up arms against his fellow Americans (“those people” in the Lee lexicon)? Of all the heroes of the Confederacy, Lee seems among the least enthusiastic about slavery, after all, even if he admittedly thought whites and blacks would be better off if they did not have to live together. This, by the way, from a man who purportedly regarded slavery as an unfortunate evil and who famously endorsed a last-ditch effort to sustain the Confederate war effort by arming slaves and rewarding the potential warriors with freedom. Some Lee hagiographers would have us believe these thoughts and actions alone make him a man who transcended his time. Korda does not go this far, but he does venture close. As Korda confirms in his examination of what has apparently become a myopic sort of litmus test of figures from American history, Lee was neither a virulent racist nor an egalitarian; he was no more and no less than a man of his age.

The most salient points in Korda’s study of Lee lie in his conclusions on his place in history and why he continues to be relevant despite his defeat and association with the barbaric institution of slavery. Through his successes and failures, his demeanor, and even his outlook, Lee became the very embodiment of the Confederate cause Southerners wanted to show the world and through which many of their descendants have for generations wanted the antebellum South and the Southern cause to be remembered. Lee is the thus the quintessential Southern martyr, the defeated but unconquered hero the South always wanted and many continue to cherish as a truly tragic figure. The essence of that historical transformation from accomplished Southern man to complicated American legend, Korda demonstrates, lies in our understanding of the oft-told but endlessly fascinating saga of the Army of Northern Virginia in whose footsteps the fate of a nation can be traced. Everything in Lee’s life and legend leads to and away from those iconic moments, much, as it might be said, do a great number of other events in American history as a whole. Clouds of Glory is a grand tour over well-trod historical ground that, despite its familiarity, manages to be engrossing, insightful and lively as it reaffirms why one of the Civil War era’s most iconic leaders is still deserving of our attention.

JMB