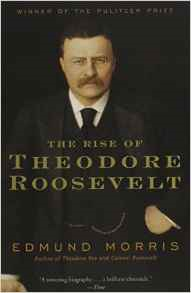

Originally published in 1979, Edmund Morris’s landmark first volume of his trilogy on the life of Theodore Roosevelt, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt, remains indisputably the foremost work on the president’s pre-White House life. I recently had the pleasure to listen to an audio recording of this acclaimed Pulitzer Prize-winning book, which many have asserted is among the iconic biographies of the modern era. I came away unable to argue the assertion.

Morris’ lengthy volume weighs in at 741 printed pages, which more than hints at the detail contained within. But merely to credit Morris with a comprehensive biography would not be giving him the credit he deserves, for his knowledge of his subject is truly incredible. He also clearly loves and admires Roosevelt. This veneration, though, is balanced by an objective presentation of the facts, leaving readers plenty of opportunity to draw their own conclusions.

That there are so many events and experiences recounted from which to arrive at those opinions is in fact the hallmark of Roosevelt’s remarkable life, for he was a man of astounding, almost surreal energy. He sometimes read multiple books in their entirety in a single night, traveled incredible distances on horseback in the wilds of the American west, indeed traveled perhaps more miles than any president before the age of aviation, and managed to produce a stunning thirty-plus books in his lifetime—all between stints as a rising political star whose service included terms as the governor of New York and as the Secretary of the United States Navy. Oh, and this father and husband tried his hand at ranching and famously led a group of “Rough Riders” to glory at the Battle of San Juan Hill (actually Kettle Hill) during the Spanish-American War. Just to read about Roosevelt is exhausting. Morris’ book will no doubt be exhausting to some as well, both in terms of its sheer length and in terms of style. It is a well-written book, but not necessarily an easy one with flowing prose. The sentences and paragraphs are dense—fittingly packing in as much content as the life of the man they chronicle. Even so, if you have interest in Roosevelt and the era in which he lived, this book should be on your reading list.

JMB