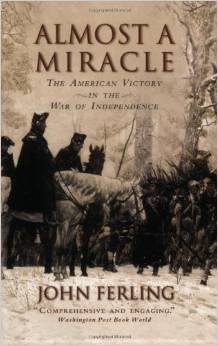

Epic!! That word not only describes the American Revolution itself, but John Ferling’s mammoth tome Almost a Miracle, The American Victory in the War of Independence. This nearly 600 page work must be the most comprehensive account of the military history of the American Revolution in existence. It is certainly among the best-written. Having taken a few months to conquer, we both feel like we have fought the war ourselves and are left rethinking many of our previous assumptions of the war.

From the war’s beginnings at Lexington and Concord to the Treaty of Paris eight years later, readers of this book are marched through the conflict with analysis interpreting battles, campaigns, and diplomacy from both the Patriot and British perspectives. The amount of material is overwhelming as Ferling traces the war in detail but surprisingly, does not get bogged down in any area. He moves quickly and deftly through even the most complex topics, keeping his narrative lively and compelling. It is hard to avoid repetition and keep a reader engaged throughout the course of a book of this length, but Ferling is a master at conveying the sights, sounds, and emotions of individual moments in time. He brings both a balance and a polish to the story that makes the book easily among the best resources on the subject available. But, this is not a quick read and anyone who wants a concise overview of the war should look elsewhere.

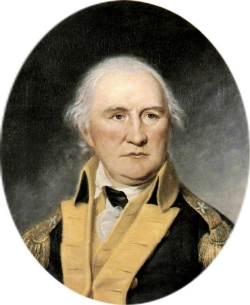

Ferling recounts all the key battles and important events that occurred during the war on battlefields, in camps, on the seas, and in the halls of Parliament and Congress. Many points in the book spark especially in-depth discussion by Ferling and are a defining aspect of the book, such as the leadership of George Washington. While it is axiomatic in many studies that Washington was the visionary that saw the Revolution to completion, readers here are left questioning the infallibility of the “Father of our Country.” Although Ferling praises his determination, courage, and virtue, he demonstrates he was not without faults. He seemed infatuated with recapturing New York after its abandonment early in the war and never fully comprehended the strategic importance of the war in the South. Many of us seem to forget that after 1778, Washington and his army were basically silent until Yorktown. And French leadership was instrumental in making even that bold stroke. Ferling heaps perhaps more praise than might be expected on Nathaneal Greene and his exploits in the South, saying no other commander played a larger role in securing victory and leaves little doubt that the Southern campaigns were pivotal in determining the war’s outcome.

The at times glaring British ineptitude in the conduct of the war also comes in for examination by Ferling. He points out that there were numerous times when a bold and energetic leader could have won a decisive victory. William Howe had several opportunities to eliminate Washington and his army in 1776 during the New York campaign and failed to seize the moment. Lord Cornwallis abandoning the Carolinas only to get trapped at Yorktown was a monumental mistake, but then again, Henry Clinton simply sat in New York and did nothing to help his subordinate.

Ferling gives careful consideration to the role of the French in securing American independence, as well. Economically, France loaned funds that propped up the country so it could survive. These loans of course led France to economic ruin and toward a revolution of their own. Militarily, the French provided critical manpower and naval forces that swung the balance of the war.

Ferling uses his last chapter of his book to evaluate just how the “miracle” of American victory occurred. Indeed, it was a long shot and at several key moments stood on the verge of faltering. It is easily the strongest part of the book. He discusses the British difficulties with a divided government and populace unsure of the value of waging war in the first place, logistical and supply difficulties, and failures of military leaders during the war. On the American side, a weak national government was the biggest hindrance to victory as the Continental army was woefully ill supplied and fed and the economic situation was in ruins—troops went for months and often years with no pay. Ferling claims point blank that American independence depended primarily on our allies from Europe. “French help was the single most important factor in determining the outcome of the War of Independence.”(564) Few Americans today truly realize how close the United States was to never happening! Besides serving as an epic narrative of the conflict, this book serves as a reminder of how fortunate we are to have become a nation in the first place.

CPW/JMB